Livingston, Montana Stands with Standing Rock

December 5, 2016, For The Livingston Enterprise

CANNONBALL, NORTH DAKOTA — For those camped out in protest against the Dakota Access Pipeline, The Army Corps of Engineers' announcement Sunday to deny the pipeline easement permit for the final section of construction across the Missouri River was a bittersweet victory for many persevering in the folds of the icy, windswept North Dakota prairie.

National Public Radio, CNN and other major news outlets followed the Corps’ statement within hours on how Energy Transfer Partners, the company behind the pipeline project, has every intention of continuing construction, albeit over a possibly alternate route.

Big Timber resident Mitchel Johnson, 24, has camped out among the protesters for nearly a month. He is a quarter Ojibwe, a Minnesota tribe, though not a registered tribal member. He considers the Corps’ decision a small victory for Standing Rock.

“I feel like the corporations are more powerful than our government,” he said.

It’s a sentiment shared by thousands who have occupied the floodplain that is the confluence of the Cannonball and Missouri Rivers in protest against the Dakota Access Pipeline. The 1,172-mile-long, $3.8 billion project is nearly complete, save for a section just north of the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation. Construction crews need only to bury the connecting stretch of pipeline beneath Lake Oahu, a reservoir formed by a dam on the Missouri, before the crude can flow.

For several months, protesters, or “water protectors,” as they call themselves, have camped out in fluctuating numbers on land managed by the Army Corps of Engineers, practically a stone’s throw north of the Standing Rock Reservation boundary, in a sign of protest.

The day after Thanksgiving, the Corps issued a statement, which in part read that any person found to be on Corps lands north of the Cannonball River after Dec. 5 will be considered trespassing and may be subject to prosecution.

North Dakota Gov. Jack Dalrymple has also issued an “emergency evacuation” order for the protesters to disperse, citing the freezing temperatures ahead. But it seems few have any intention of leaving.

A helicopter circles over the Dakota Access Line protest camps lining North Dakota Highway 1806 as night falls on December 3, 2016.

Livingston man Danny Freund of the band The Bus Driver tour is pictured along side his bus at the Oceti Sakowin camp on December 4, 2016. He installed a wood stove in the back and modified the seats to serve as beds. He calls it “The Heat Machine.”

Boyfriend and girlfriend Danny Freund and Flannery Coats of Livingston, Montana are pictured inside Freund’s school bus, modified into living quarters, at the Oceti Sakowin camp on Dec. 4, 2016. The couple has made multiple trips to the Dakota Access Pipeline protest camps, distributing hundreds of pounds of donated food and supplies.

On Sunday, the population of Oceti Sakowin, the largest of the protest encampments, swelled well past several thousand as a non-stop line of vehicles inched their way in from the south.

Among those returning to camp was Livingston resident Margo Kidder, who raised her fist in solidarity from her car on the highway when she heard the news.

“This is great!” she proclaimed.

By nightfall, cars, buses and trucks were at a near standstill, backed up at least a mile and over the hill out of sight. The prospect of sub-zero temperatures forecasted for Monday night does not seem to have deterred many.

Meanwhile, a trio of massive live-broadcast satellite trucks sat on the highway, hundreds of camera-wielding journalists and documentarians swarmed over the roadway, and in every space between the tepees, tents, cars, campers and buses parked in the drifting snow, just in time for the tribe’s initial celebratory reaction to the Corps’ announcement.

The eyes of the world were, and still are, on Standing Rock.

Oceti Sakowin is one of several sprawling camps entrenched along North Dakota Highway 1806, 45 miles south of the state capital, Bismarck. Protesters from all over the country and the globe have flowed in and out of the camps.

Livingston resident and actress Margot Kidder looks back at her dog, Zack, and suggests he raise a paw in solidarity after Kidder received the news the Army Corps of Engineers denied the easement permit for the Dakota Access Pipeline to cross the Missouri River on December 4, 2016 as she inches her way up highway 1806 into camp.

Among them are dozens of Montanans from Livingston and surrounding areas, some of whom have made multiple trips and camped out for weeks at a time, bringing along hundreds of pounds of supplies in support of the water protectors.

Danny Freund, of Livingston’s Bus Driver Tour band and his girlfriend, Flannery Coats — owner of Livingston Bodega and Bakery, a Main Street business — on Saturday returned to Oceti Sakowin in Freund’s large white school bus. To cope with the increasingly cold conditions, Freund installed a wood stove in the back of the bus. The stove pipe pokes out through the ceiling’s emergency exit.

Painted on the side of bus in flowing letters is “Min Wiconi,” the Lakota language’s phrase for “Water is Life.” Freund calls his bus “The Heat Machine.”

Easy to spot in the sea of tents and vehicles, the bus serves as a meeting place and a base of operations for the Livingston contingent.

Freund and Coats have gathered, delivered and donated hundreds of pounds of meat and other essentials.

Traveling with the couple is Livingston’s Lisa Talcott, 63, a social worker employed at Livingston HealthCare. Her great-great grandparents homesteaded in the Paradise Valley. It’s her first time at camp.

“I was at home and just watching what was going on out there,” said Talcott. “I felt helpless.”

Talcott plans to apply her professional skills as a volunteer at Oceti Sakowin’s mental health tent.

“I think this is an important time in history in general and this country,” she said, “Lots of civil rights violations happening out here.”

Talcott and her sister were raised by their single mom, Shirley, whom Talcott described as a fiercely independent woman and an unabashed activist. Her mother marched with Martin Luther King in 1965 at Selma.

“Her doing that left a huge impact on my sister and I,” Talcott said.

She felt inspired to follow in her mother footsteps some day.

“So this is for my Mom,” she said, tears welling up behind her glasses.

The Morton County Sheriff’s office, aided by the North Dakota National Guard, has led the area’s law enforcement effort.

Highway 1806 remained blocked with concrete barrier and razor wire over the weekend about a quarter of a mile north of Oceti Sakowin. One armored police vehicle and a couple dozen police cars were parked at the roadblock on Saturday evening, but no police stood out in the open.

Across the Cannonball on a bluff known as Turtle Island, police also had erected harsh, white lights, which shin into camp by night. Additional lights blaze in the hills beyond the river, illuminating the pipeline construction route. Helicopters and small planes circled low over the camp at all hours.

Native Americans had many anecdotes to share about their encounters with law enforcement, recounting instances of rubber bullets and bean-bags fired on protesters at police blockades.

Walter Brave, an Oglala Lakota from South Dakota, painted his face red, yellow, white and black in the rear view mirror of “The Heat Machine” on Sunday night by the light of a propane lantern, stating he was “ready to go into battle if needed.”

He said he was among the first to come to the aid of a young woman on the night of Nov. 20, during a particularly heated clash between police and protesters. National Public Radio reported the name of the woman as 21-year-old Sophia Wilansky and reported her injury as so severe she might lose her arm.

Walter Brave, an Oglala Sioux, from South Dakota applies red battle paint to the top half of his face in the rearview mirror of Danny Freund’s bus at Oceti Sakowin on Dec. 4, 2016, the largest of the Standing Rock Sioux water protector camps protesting the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline near the confluence of North Dakota’s Cannonball and Missouri Rivers.

Brave said she was struck in the arm by an exploding “concussion grenade” and he helped carry her away from the front lines to safety.

Drone footage broadcasted by major news outlets showed police spraying protesters with fire hoses after dark in freezing temperatures that night.

The message from the Native Americans and other water protectors at camp is consistent: They want to maintain peace and prayer. The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s prevailing concern is that the pipeline poses undue risk to their reservation’s water supply. Rallying cries of “Mni Wiconi!” rippled across camp in a series of shouts throughout the day.

Camped adjacent to The Heat Machine is Standing Rock Tribal Councilman Dana Yellow Fat, 45, and his family. He sports a NODAPL baseball cap.

Freund offered him a cigarette, which he readily accepted.

“We decided to take this,” said Yellow Fat, sweeping his hand to the north in reference to the Army Corps Land now occupied by the protesters. “So we took it.”

While the Cannonball River is the federally recognized northern boundary of The Standing Rock Sioux Reservation, Yellow Fat said Standing Rock claims a huge swath of territory stretching nearly to Bismarck and west across North Dakota and into Montana and is unceded land under the 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty.

According the U.S. Department of Transportation’s National Pipeline Mapping System website, the Dakota Access Pipeline would follow an existing gas line under the river.

Yellow Fat was arrested with Standing Rock Sioux Chairman Dave Archambault during an Aug. 11 protest rally, according to the Bismarck Tribune.

The flags of hundreds of different indigenous nations from around North America and the world fly in the sun over the Ocet Sakowin camp on Dec. 4, 2016.

“I started this. I got arrested and social media blew up,” he said.

Freund inquired about a notion that the tribe was offered money by the pipeline company for the construction of the line along its currently planned route.

“We didn’t get offered any money,” Yellow Fat said. “They came to our council meeting two years ago, and we opposed it then.”

Other Livingston residents’ reasons for visiting are less ardent than the Native Americans at camp and their legions of sympathizers.

“I’m really just here to see what’s going on,” said Livingston resident Elijah Isaly, “and see it with my own eyes.”

He said his mother, Traci Isaly, has made multiple trips to camp.

If the steady lines of incoming traffic aren’t enough of an indication of the booming numbers at the camp, the conical mounds of frozen human waste poking over the lips of the porta-potty seats are a sure sign of an over-congested shantytown.

That smell aside, the air was filled with the scents of sage, wood smoke and a whiff or two of marijuana. The camp holds a strict no-drugs-and-alcohol policy.

The maze of roads connecting the camp are deeply rutted lanes of frozen mud. Painful slips and falls are common. A large white tour bus trying to leave the camp had to be chained to a front loader and hauled up the hill to the highway.

Under the crisp skies over camp, clouds of exhaust drifted from the tail pipes of the thousands of periodically idling cars, their occupants attempting to keep warm. Numerous petroleum-based products have proved indispensable to the survival of protesters, made only more invaluable by the harsh conditions. It’s unlikely so many water protectors could have gathered in the middle of the unforgiving North Dakota grasslands without propane heat, the combustion engines in snow removal equipment or the trucks delivering food, water, blankets, medical supplies and firewood through America’s least-forested state.

A sharp, rising crescent moon silhouetted the tepee poles and the flags of hundreds of indigenous nations lining the central avenue into Oceti Sakowin. A few rounds of fireworks exploded overhead. Next door to The Heat Machine, Councilman Yellow Fat and his friends and family gathered around their fire, pounding drums, smiling as they sang.

Standing Rock may have won the day, but the Native Americans’ historic stand for their water and sovereignty is on track to play out on the prairie near Cannonball in the days, weeks and even months to come.

Inside the Heat Machine, after a dinner of Sloppy Joes prepared by Coats of Livingston, Johnson of Big Timber warmed himself by the fire.

“You gotta have hope,” he said, gazing into the flames, “Even if we don’t stop them, we have the honor of trying.”

Blizzard Strikes: Locals hunker down

December 6, 2016, For The Livingston Enterprise

CANNONBALL, NORTH DAKOTA –– By late Monday morning, the snow started to fall. And with it came the wind — inescapable and relentless, stinging any patch of exposed human skin into numbness on the North Dakota prairie.

But the day before, hundreds of veterans — native and non-native — had arrived from around the country, as they promised they would. Their self-assigned mission: to act as an added layer of protection for the water protectors demonstrating against the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline under the Missouri River near the northern boundary of the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation.

In the first couple of hours of the blizzard, temperatures rose into the high 20s, leaving thick sheets of wet flakes to pelt the procession of hundreds of veterans, Sioux, other demonstrators and journalists on their march north along Highway 1806 to the police barricade, a series of jersey barriers and razor wire, beyond which are Dakota Access Pipeline construction areas.

The veterans marched carrying a dozen large flags, their eyes squinted against the blowing snow. A handful of other demonstrators waved banners inscribed with “Water is Life,” or “Mni Wiconi,” the Lakota translation of the phrase. Native American-style drums and chanting echoed out toward the roadblock.

No law enforcement officers were to be seen, although a line of Sioux and other camp volunteers kept the mass at about 100 yards from the blockade on Backwater Bridge.

Despite the brutal wind, their repeated rallying cries of “Mni Wiconi!” rang out clear over the crowd.

After chanting and drumming for about an hour, the procession made an about-face and shuffled the short distance down the highway back to camp.

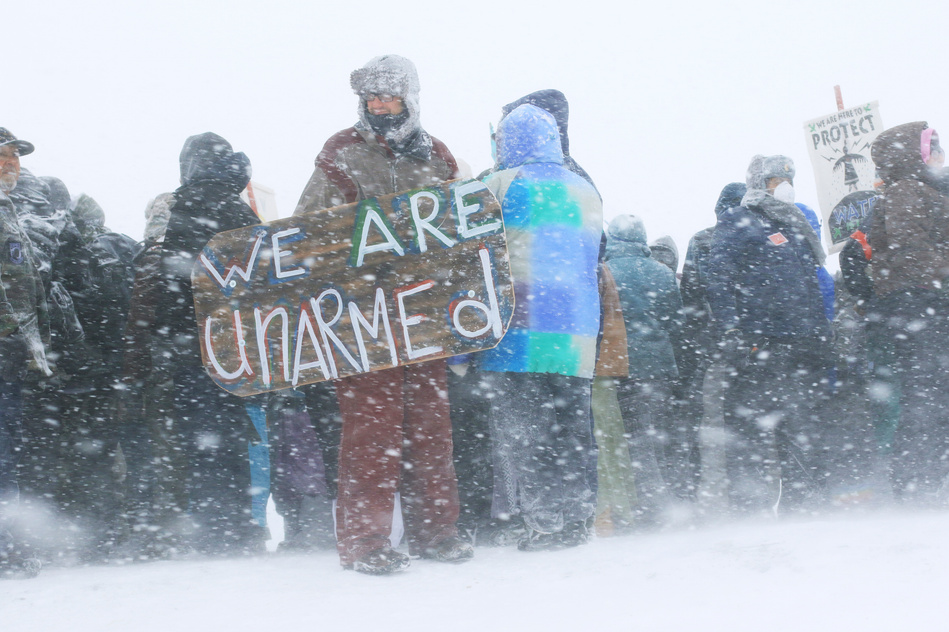

A protestor holds a sign trough the blizzard conditions during the veterans march on Highway 1806's Backwater Bridge just north of the Oceti Sakowin camp on Dec. 5, 2016.

Penned in by the storm

It was evident by Monday afternoon the blizzard blowing across the Dakotas was a potentially life-threatening storm. Anyone trying to leave from that point onward would do so at their own peril, including Livingston residents and other Montanans still stuck in North Dakota.

The word around camp was that Standing Rock Sioux Tribe Chairman David Archambault III has asked protestors to disband and all who are not Sioux to return home as soon as possible.

As reported by Reuters late Monday, Archambault said, “We’re thankful for everyone who joined this cause and stood with us. The people who are supporting us … they can return home and enjoy this winter with their families. Same for law enforcement. I am asking them to go.”

But the North Dakota Department of Transportation has issued a no-travel advisory for about 15 counties across the state, including Morton County, the site of Oceti Sakowin.

“Eight degrees!” said Danny Freund, of Livingston, climbing back into the bus after reading the outdoor thermometer after sundown on Monday, his hair sticking every which way from a combination of hat-hair and the 50 mph gusts.

Wind chill temperatures dropped to -20 degrees. The Bismarck Tribune reported Interstate 94, the most direct path home for Montanans, was closed from Dickinson to Jamestown as of Monday evening and remained closed through Tuesday morning. The Sioux volunteers managing the camp advised people not leave and shelter in place until conditions improve.

ABOVE: Veterans wielding flags march on Highway 1806's Backwater Bridge just north of the Oceti Sakowin camps as a blizzard blows in Dec. 5, 2016.

RIGHT: A protestor positions himself head and shoulders over the crow waving an American flag bearing a peace sign during the veterans march on Highway 1806's Backwater Bridge, the site of the police barricade.

Many people decided to risk it and head out on roads that hadn’t yet been closed, including Lisa Talcott, of Livingston. She made it only as far as Prairie Knights Casino & Resort, about 10 miles south of the camps.

“Casino is packed,” she reported via text message. “Nowhere to sit except the floor. Roads are just sheets of ice.”

A speaker at the camps’ Seven Sacred Fires, a centralized area for prayer and important announcements, reported at least 17 cars had slid off the highway in their attempts to leave.

Meanwhile at camp, tents had collapsed and at least one bus overturned in the wind.

Meriweather Campbell, Sally O’Connor and Elijah Isaly, who traveled out to Standing Rock over the weekend in Isaly’s truck, made it only as far as Mandan before the Interstate was closed.

As the first flakes of the storm fell Monday morning, O’Connor, former executive director of the Livingston HealthCare Foundation, sipped coffee with Isaly and Campbell on the tailgate of Isaly’s truck.

“We can sit here and watch this happen,” she said. “Or go and be a part of it. The fact that this many people are coming here from all walks of life is a pretty powerful thing.”

From left, Livingston residents Meriweather Campbell, Sally O’Connor and Elijah Isaly huddle over some coffee on Dec. 5, 2016 as the first flakes of a storm begin to fall. A blizzard has since swept over the Dakotas, bringing snow, whiteout conditions, single-digit daytime temperatures, gusts up to 50 mph and closed roads.

Trying to keep warm and supplied

Freund drove a modified, well-stocked school bus out to Standing Rock on Saturday. He calls it The Heat Machine. It’s fitted with a handsome wood stove at the rear — an oasis of relative warmth in the drifting dunes of white. Even so, the bus’ supply of water jugs were nearly frozen solid by morning.

Wisps of white breath flowed like puffs of steam out from Walter Braves’ sleeping bag across the aisle. An Ogala Lakota from South Dakota, Brave has stayed at the camps since Aug. 17 and since has befriended Freund and his girlfriend, Flannery Coats.

The couple has made several trips to Standing Rock since the summer, collecting and distributing hundreds of pounds worth of food and other donations.

Tuesday morning, Talcott called back to camp to check in. The situation at the casino remained packed, with every room packed to capacity and hundreds sleeping on the floor of the halls and into the casino’s pavilion, among them many veterans.

Talcott said there was growing concern about the food delivery truck coming in time to restock the casino.

“When I was driving to the casino yesterday, I thought: ‘This is the kind of weather people die in,’” she said.

A medic stopped by the Heat Machine on Tuesday morning and said they were overwhelmed with people in need of shelter and warmth. Freund and Coats began preparing the bus to serve as a warming station to those in need for later in the day.

A brief break in the blizzard reveals a saturated sunset over the Oceti Sakowin camp on Dec. 5, 2016.

The Corps and the protesters

For months, thousands of people have set up camp near the confluence of the Cannonball and the Missouri rivers. The demonstrators’ largest camp, Oceti Sakowin, is on land managed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

The Corp on Sunday denied the key easement that would legally allow Energy Transfer Partners, the company behind the pipeline, to drill beneath the Missouri and connect the final section of line to the completed length on the other side. But not before the Corp issued a statement the day after Thanksgiving ordering the demonstrators to abandon their camps north of the Cannonball River, or face arrest.

The statement read, in part: “Any person found to be on the Corps’ lands north of the Cannonball River after December 5, 2016, will be considered trespassing and may be subject to prosecution under, federal, state, and local laws.”

On Tuesday, Dec 6, the mercury on the side of The Heat Machine read 4 degrees, the wind raging unabated.

Those now camped along the Cannonball River have little choice but to hunker down –– be it in defiance of the law or simply in an effort for survival.

Journalist Joe Whittle, a member of the Caddo Nation, takes a personal moment of prayer in front of the police barricade at the Backwater Bridge on Highway 1806 on Dec. 6, 2016 as a lone police car watches over the bridge the day after the Army Corp of Engineers denied Energy Transfer Partners the easement to lay the pipeline under the Missouri River. Whittle said he prayed for forgiveness for the police who fired rubber bullets at daughter, Mia, a Stanford University student as she was kneeling on the ground herself in prayer on the night of November 20, 2016. That night, one of the most heated clashes of the Standing Rock saga between protestors and law enforcement occurred. In addition to the use of rubber bullets, tear gas, and other projectiles, police also sprayed protesters with fire hoses in the freezing temperatures, leading to multiple cases of hypothermia.